Francis Grose

The Georgian soldier and antiquarian Francis Grose (1731-1791) wasn’t cut from the usual cloth of which lexicographers are made.

The Georgian soldier and antiquarian Francis Grose (1731-1791) wasn’t cut from the usual cloth of which lexicographers are made.

In order to research words and phrases for his dictionaries he bypassed the scholarly works in the local library and headed straight for the back-streets.

Grose was an enthusiastic, but untutored, researcher into historic artefacts and language, who believed that the language belonged to the people. His aim was to record the way people spoke, not how they were supposed to speak. His indefatigable inquiries have left us with a unique record of the English language, as it was spoken in Georgian England.

Grose revelled in the lives and language of the underworld. He was down to earth and often bawdy, but as a linguistic man of the people rather than a rogue. He published numerous works on many subjects and was a friend to many notables of his day, including Robert Burns and the painter Christopher Pack.

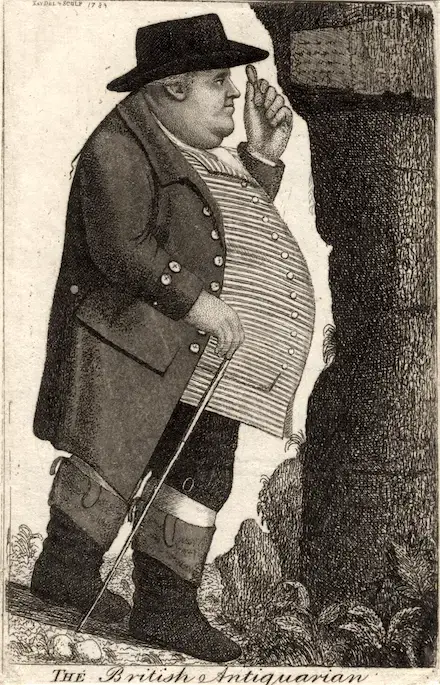

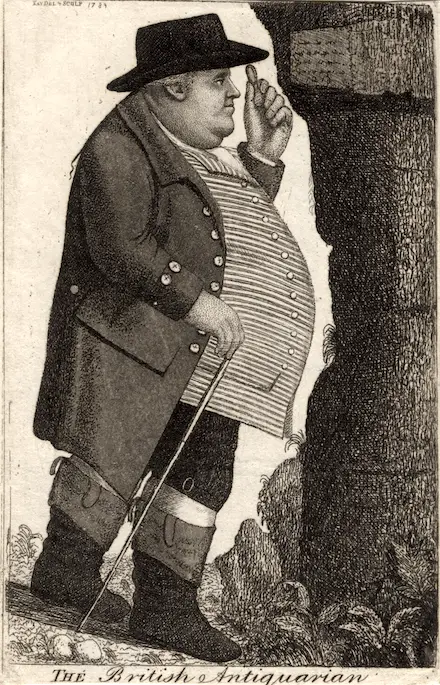

Pack described his appearance as “Five feet high and weighing twenty-two stone, with a coat cut in the fashion of thirty summers ago.”.

Other lexicographers made formal dictionary definitions of words or studied particular trades or callings. For example:

– Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language

– Admiral William Smyth’s The Sailor’s Word-Book

– Randle Cotgrave’s A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues

Those works are very useful to modern-day research but they cover specialist ground. What Grose gave us was a collection of dictionaries that recorded the everyday speech of people of all trades and stations in life. Had he not down so, much of that speech, which not put into print, would now be lost to us.

While works like Pride and Prejudice give us a picture of Georgian England as glimsped through net curtains, Grose’s dictionaries take us out into the streets and alleys.

His most important work, the Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1785, is a boon to etymologists.

The Oxford English Dictionary refers to his two most noted dictionaries 1,132 times, recording such words as:

– Able wackets: “Blows given on the palm of the hand with a twisted handkerchief.”.

– To funk the cobbler: “To fill a room or other closed space with foul-smelling smoke as a prank.”.

– Slush-bucket: “One that eats much greasy food.”.

Those aren’t part of the language any longer, although it might be thought of as something of a loss. However, Grose’s glossaries are by no means a list of obsolete words. He was the first to record numerous expressions that survive as everyday language, including:

Cut off your nose to spite your face

Who knows that, if Grose hadn’t haunted the taverns and markets of 18th century England, whether we would still be using those phrases.

Sorry, must go now. I’m off to funk the cobbler.