A proverbial saying, often used in circumstances where it is thought that saying nothing is preferable to speaking.

Silence is golden

What's the meaning of the phrase 'Silence is golden'?

What's the origin of the phrase 'Silence is golden'?

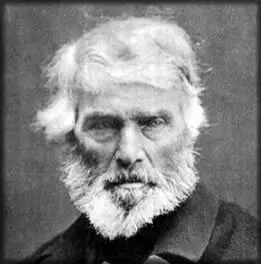

As with many proverbs, the origin of this phrase is obscured by the mists of time. There are reports of versions of it dating back to Ancient Egypt. The first example of it in English is from the poet Thomas Carlyle, who translated the phrase from German in Sartor Resartus, 1831, in which a character expounds at length on the virtues of silence:

“Silence is the element in which great things fashion themselves together; that at length they may emerge, full-formed and majestic, into the daylight of Life, which they are thenceforth to rule. Not William the Silent only, but all the considerable men I have known, and the most undiplomatic and unstrategic of these, forbore to babble of what they were creating and projecting. Nay, in thy own mean perplexities, do thou thyself but hold thy tongue for one day: on the morrow, how much clearer are thy purposes and duties; what wreck and rubbish have those mute workmen within thee swept away, when intrusive noises were shut out! Speech is too often not, as the Frenchman defined it, the art of concealing Thought; but of quite stifling and suspending Thought, so that there is none to conceal. Speech too is great, but not the greatest. As the Swiss Inscription says: Sprecfien ist silbern, Schweigen ist golden (Speech is silvern, Silence is golden); or as I might rather express it: Speech is of Time, Silence is of Eternity.”

That fuller version – ‘speech is silver; silence is golden’, is still sometimes used, although the shorter form is now more common.

The same thought is expressed in a 16th century proverb, now defunct – as many present-day feminists would prefer it:

“Silence is a woman’s best garment.”

Silence has in fact long been considered laudable in religious circles. The 14th century author Richard Rolle of Hampole, in The psalter; or psalms of David, 1340:

“Disciplyne of silence is goed.”

Wyclif’s Bible, 1382 also includes the thought – “Silence is maad in heuen”. [made in Heaven]

The history of “Silence is golden” in printed materials

Trend of silence is golden in printed material over time

Browse more Phrases

About the Author

Phrases & Meanings

A-Z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T UV W XYZ

Categories

American Animals Australian Bible Body Colour Conflict Death Devil Dogs Emotions Euphemism Family Fashion Food French Horses ‘Jack’ Luck Money Military Music Names Nature Nautical Numbers Politics Religion Shakespeare Stupidity Entertainment Weather Women Work

How did we do?

Have you spotted something that needs updated on this page? We review all feedback we receive to ensure that we provide the most accurate and up to date information on phrases.